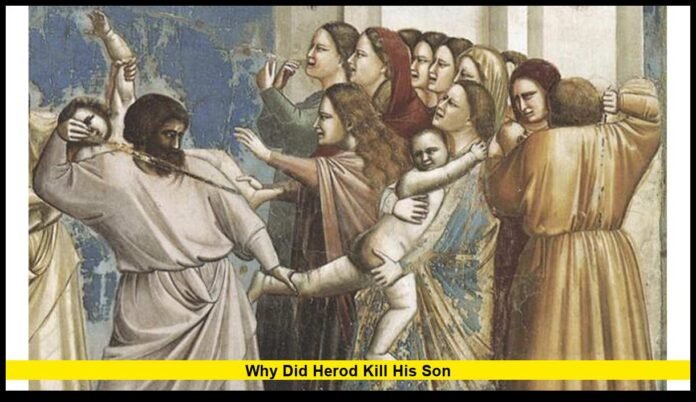

The question “why did Herod kill his son” has fascinated historians and Bible scholars for centuries. The answer lies in one man’s consuming fear of losing power. Historical evidence confirms that King Herod the Great, who ruled Judea under Roman authority, killed several of his sons out of suspicion that they were plotting to overthrow him.

Herod’s actions were not random acts of cruelty — they were calculated decisions driven by paranoia, jealousy, and political insecurity. His reign, marked by both monumental achievements and personal tragedy, remains one of the most studied in ancient history.

The Background: Who Was Herod the Great?

King Herod the Great ruled Judea from 37 BCE to 4 BCE, under appointment from the Roman Senate. He is remembered for his extraordinary architectural projects, including the expansion of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, the fortress at Masada, and the palace complex known as Herodium.

But behind these accomplishments was a man consumed by insecurity. Herod’s position as king depended on Rome’s favor, not popular support. His Idumean (Edomite) ancestry meant that many Jews viewed him as an outsider, not a legitimate ruler.

This fragile legitimacy planted the seeds of paranoia that would eventually drive him to kill members of his own family.

The Sons Who Died at Herod’s Command

Herod had at least ten wives and numerous children, which created constant tension over succession. Three of his sons met their deaths by his order:

Alexander and Aristobulus IV

These two sons were born to Mariamne I, a Hasmonean princess and Herod’s second wife. Mariamne’s royal lineage gave her sons strong claims to the throne — a fact that both elevated and endangered them.

Herod adored Mariamne but later grew suspicious of her loyalty, eventually having her executed. After her death, his distrust extended to their sons. Court insiders began spreading rumors that Alexander and Aristobulus planned to avenge their mother’s death by overthrowing their father.

Herod, already plagued by fear of rebellion, ordered a trial. Despite a lack of evidence, both sons were executed in Sebaste (Samaria) around 7 BCE.

Herod’s eldest son, Antipater, was born to his first wife, Doris. Initially, Antipater was Herod’s most trusted heir and enjoyed special privileges. However, as Herod aged, he began hearing whispers that Antipater was plotting to poison him.

Furious and paranoid, Herod stripped Antipater of his inheritance, imprisoned him, and later had him executed in 4 BCE — just days before Herod himself died.

Why Did Herod Kill His Son? The Deeper Causes

The reasons behind Herod’s decision to kill his sons can be traced to three main factors: fear of betrayal, insecurity about legitimacy, and the corrupting nature of absolute power.

Fear of Losing the Throne

Herod’s greatest fear was being overthrown. His power came from Roman approval rather than from the will of the Jewish people, which made him constantly anxious about rebellion.

When rumors reached him that his sons were plotting to seize power, he viewed them not as family but as political enemies. Even without solid proof, his instinct for self-preservation drove him to eliminate the perceived threat.

Political Insecurity and Lineage

Herod’s Idumean background made his position unstable. He married Mariamne I partly to connect himself to the Hasmonean royal family — the previous Jewish ruling dynasty.

But that marriage created a new problem: his sons by Mariamne had a purer royal lineage than Herod himself. Many in Judea saw them as the rightful heirs. Herod feared that their noble blood might inspire rebellion, leading him to view them as rivals rather than successors.

Paranoia Fueled by Manipulation

Herod’s later years were marked by paranoia, intensified by the scheming of courtiers who sought to manipulate him. Advisors spread lies and accusations, convincing him that his sons plotted treason.

Instead of investigating rationally, Herod acted out of emotion and fear. Once his trust was broken, it was impossible to restore.

Herod’s State of Mind: Power, Illness, and Decline

Historians describe Herod as a ruler who combined great intelligence with extreme volatility. In his final years, his mental and physical health deteriorated. Records from Flavius Josephus, the first-century historian, describe Herod’s severe illnesses and erratic behavior.

Some medical researchers today suggest he may have suffered from chronic kidney disease, hormonal disorders, or infections that affected his mood. However, his decisions were still deliberate acts of political control — not random insanity.

Herod’s paranoia was amplified by his isolation. Surrounded by spies and flatterers, he trusted no one. Even his own children became potential conspirators in his mind.

Reactions from Rome and the Ancient World

Herod’s actions shocked the ancient world. His brutality was so notorious that even Emperor Augustus reportedly joked, “It’s better to be Herod’s pig than his son.”

The dark humor behind the remark was clear: Herod, who followed Jewish dietary laws that forbade eating pork, would never harm a pig — but he had no hesitation killing his own children.

Herod’s violence weakened his dynasty. After his death, Rome divided his kingdom among surviving sons and governors, effectively ending his dream of a lasting royal legacy.

Historical Confirmation: The Records of Flavius Josephus

The most detailed account of these events comes from Flavius Josephus, a Jewish historian writing under Roman patronage in the first century CE. His works Antiquities of the Jews and The Jewish War describe Herod’s rule in vivid detail.

Josephus documented the trials, executions, and the climate of fear that surrounded Herod’s court. Modern scholars continue to use his writings as primary historical evidence, supported by Roman records and archaeological discoveries.

Archaeological studies at Herodium, Herod’s palace and tomb site, have helped verify many aspects of his reign, including his wealth, power, and obsession with control.

Legacy of Fear and Tragedy

Herod’s decision to execute his sons destroyed his family and forever stained his reputation. His reign offers a striking example of how fear and ambition can consume even the most powerful rulers.

After his death in 4 BCE, Judea was divided among his surviving heirs:

- Archelaus governed Judea, Samaria, and Idumea.

- Herod Antipas ruled Galilee and Perea.

- Philip oversaw territories in the north and east of the Jordan.

None of them achieved their father’s level of power or influence. Within decades, Rome absorbed Judea into its empire, ending the Herodian dynasty’s autonomy.

Why Herod’s Story Still Matters

The story of Herod’s family tragedy continues to resonate today because it reflects a timeless truth: unchecked power can destroy even the closest bonds.

The question “why did Herod kill his son” reveals more than an act of cruelty — it exposes how absolute authority, when combined with insecurity, leads to moral collapse.

Herod’s life reminds modern readers that leadership without trust or compassion becomes tyranny. Despite his architectural achievements and political cunning, history remembers him most for his fear-driven violence and the destruction of his own family.

Herod killed his sons out of paranoia, pride, and the desperate need to protect his throne. His story endures as a warning about the dangers of power without conscience. What are your thoughts on Herod’s legacy? Share your views below!