The question “Did Herod kill his son?” has intrigued historians, theologians, and everyday readers for more than two millennia. The answer, supported by multiple historical records, is yes — King Herod the Great ordered the execution of several of his own sons.

Herod’s decision to kill his children stemmed from deep paranoia, political insecurity, and a relentless desire to protect his power. His actions shocked even his Roman allies and have become emblematic of the destructive lengths some rulers went to in the ancient world to maintain control.

As of December 2025, this dark chapter in history remains a subject of detailed study. Modern historians and archaeologists continue to uncover insights about Herod’s reign, confirming the brutality that marked his rule and the tragic fate of his family.

Who Was Herod the Great?

King Herod the Great ruled Judea from 37 BCE to 4 BCE under the authority of Rome. Appointed “King of the Jews” by the Roman Senate, Herod was known as both a master builder and a merciless monarch.

He oversaw the reconstruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, built fortresses like Masada and Herodium, and developed new cities such as Caesarea Maritima. His architectural legacy was monumental, but his reign was marred by cruelty and fear.

Herod’s ambition to secure power at all costs led him to commit atrocities, including the killing of close relatives — actions that historians say define his legacy as both brilliant and brutal.

Herod’s Rise to Power and Deep Insecurities

Herod came from an Idumean (Edomite) background, a lineage viewed by many Judeans as foreign. Though his family converted to Judaism, his non-native roots made him an outsider to the people he ruled.

Herod’s rule was secured through Rome’s backing rather than popular support, which made him perpetually insecure. Every potential rival — whether political or familial — became a target of suspicion.

As Herod grew older, that fear turned into obsession. He believed conspiracies surrounded him, even within his own home. Family members, courtiers, and even his sons were accused of treachery, often based on little or no evidence.

The Family Herod Destroyed

Herod’s personal life was as complex as his politics. He married at least ten women, each from powerful or politically advantageous backgrounds. His marriages often tied him to rival royal families — alliances that later became sources of paranoia.

His most famous wife, Mariamne I, came from the Hasmonean dynasty, the former rulers of Judea. Their marriage was both romantic and political, designed to strengthen Herod’s legitimacy. Yet it would ultimately lead to tragedy.

The Sons Who Died by Herod’s Order

Historical accounts confirm that Herod executed at least three of his sons: Alexander, Aristobulus IV, and Antipater III. Each death reflected Herod’s descent into mistrust and his fear of losing power.

Alexander and Aristobulus IV

Alexander and Aristobulus were the sons of Mariamne I. Their Hasmonean bloodline made them legitimate heirs in the eyes of the Jewish people — something Herod viewed as dangerous.

Initially, Herod sent both sons to Rome to be educated, where they gained respect and favor among Roman elites. Upon their return to Judea, rumors began circulating — likely spread by Herod’s advisors — that the young men were plotting to overthrow their father.

Unable to separate truth from manipulation, Herod ordered a trial. Despite weak evidence, both sons were convicted of treason. In 7 BCE, Herod had them executed in Sebaste (Samaria).

The historian Flavius Josephus later wrote that Herod was overcome with guilt and grief after their deaths, but his paranoia prevented him from reversing the decision.

Antipater III

Antipater, Herod’s eldest son from his first wife, Doris, initially stood as heir to the throne. Herod trusted him deeply — until whispers began that Antipater was plotting his father’s death.

Convinced of his guilt, Herod stripped him of his privileges, imprisoned him, and eventually ordered his execution in 4 BCE — just days before his own death.

Josephus recorded that the Romans were horrified by Herod’s actions. Even Emperor Augustus reportedly commented, “It’s better to be Herod’s pig than his son.” The remark mocked Herod’s observance of Jewish dietary laws, which forbade eating pork — suggesting that his children were less safe than his livestock.

Why Did Herod Kill His Sons?

Herod’s motives were a combination of political insecurity and psychological instability.

He constantly feared losing power, and his mind was plagued by suspicion. He believed that those closest to him — his wives, children, and advisors — were conspiring against him.

This paranoia was likely worsened by illness and age. Scholars believe that by his later years, Herod suffered from severe physical and mental decline, including chronic pain and mood swings.

Still, his killings were not random. Each execution served a political purpose — to remove anyone who could challenge his authority. To Herod, preserving power justified any act, no matter how brutal.

Herod’s Court: A Palace of Fear

By the final decade of his reign, Herod’s court had become a dangerous environment. His family lived under constant surveillance, and even the slightest accusation could lead to imprisonment or death.

He had already executed his beloved wife Mariamne I, her mother Alexandra, and several other relatives years before. These acts left his remaining children terrified and divided, each uncertain of their standing.

Josephus described Herod’s palace as a place “where suspicion ruled more than loyalty.” The atmosphere of betrayal and fear consumed everyone who lived there.

What Historians and Archaeologists Confirm Today

Modern historians have verified the historical accuracy of Herod’s actions through the writings of Flavius Josephus, supported by Roman records.

Josephus’ accounts in The Jewish War and Antiquities of the Jews remain the primary sources detailing Herod’s life. While written decades after his death, they are considered credible and consistent with other known events from the Roman era.

Archaeological research continues to add depth to our understanding of Herod’s reign. Excavations at Herodium, Herod’s palace-fortress and eventual burial site, have revealed structures, inscriptions, and artifacts that reflect his wealth, ambition, and obsession with control.

Though no direct archaeological evidence ties to the deaths of his sons, the discoveries confirm Herod’s extravagant lifestyle and complex personality — a mix of brilliance and insecurity.

The Aftermath of Herod’s Death

Herod died in 4 BCE in his palace at Jericho after a long and painful illness. By that time, he had already destroyed much of his own family through execution and exile.

After his death, his kingdom was divided by Rome among his surviving sons:

- Archelaus became ruler (ethnarch) of Judea, Samaria, and Idumea.

- Herod Antipas governed Galilee and Perea.

- Philip was made tetrarch of Iturea and Trachonitis.

None of them ever achieved the power or legacy of their father. Herod’s dynasty quickly declined under Roman oversight, and within a few decades, Judea came under direct Roman rule.

His paranoia ensured his family’s collapse — the very fate he sought to avoid.

Herod in Religious and Cultural Memory

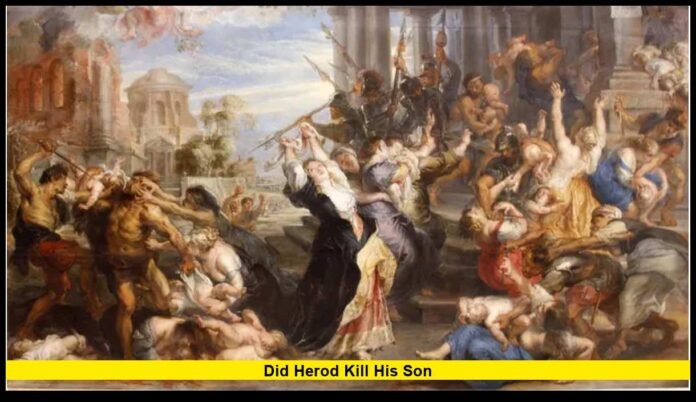

In Christianity, Herod the Great is also remembered for the Massacre of the Innocents — an event described in the Gospel of Matthew, where Herod allegedly ordered the killing of all male infants in Bethlehem after hearing about the birth of Jesus.

While historians debate the scale or even existence of that event, it fits perfectly with what is known of Herod’s character. A ruler who killed his own sons to protect his throne would have had no hesitation in committing broader acts of violence to preserve his power.

In Jewish history, Herod’s legacy remains equally conflicted. He is remembered both as the builder of the Second Temple — one of the most significant religious structures in history — and as the king who murdered his family in a desperate bid to keep his crown.

Herod’s Psychological Profile: Power and Paranoia

Modern scholars studying Herod’s life describe him as suffering from a mix of paranoia and megalomania. His obsession with control consumed every aspect of his existence.

Some researchers suggest that Herod’s condition may have been worsened by chronic illnesses like kidney disease or hormonal disorders that can affect mood and behavior.

Still, his cruelty cannot be explained away by illness alone. Herod was fully aware of his actions and executed them with calculated precision — an indication of political ruthlessness rather than madness.

Why the Story Still Matters

The question “Did Herod kill his son?” endures because it captures the ultimate tragedy of power without conscience. Herod’s decision to destroy his own family out of fear shows how absolute authority can corrupt human morality.

His story is not just about ancient history — it’s a timeless reflection on leadership, ambition, and the dangers of paranoia.

Herod’s reign stands as a warning that unchecked power, when guided by fear instead of wisdom, can destroy not only nations but families and legacies.

Yes, Herod did kill his sons — a fact recorded by history and remembered through generations. His reign, filled with triumphs and terror, reminds us how fear and ambition can turn greatness into tragedy. What lessons do you take from Herod’s story? Share your thoughts below.